The Digital Mirror of Ancient Grandeur

In an age dominated by digital innovation and fleeting trends, we often seek meaning in the complex algorithms and interconnected networks that define our modern existence. Yet, a profound wisdom often lies in the enduring legacies of the past. Consider the challenges faced by architects and engineers today: balancing grand vision with practical constraints, integrating complex systems, and ensuring long-term resilience. Indeed, these are not new problems. Millennia ago, civilizations grappled with similar dilemmas, albeit with different tools.

Timeless Challenges and Modern Parallels

For those of us navigating the intricate landscapes of technological implementation – from deploying machine learning models to orchestrating large-scale cloud migrations – the echoes of ancient grand projects resonate deeply. Consequently, we understand the frustration when a meticulously planned initiative yields only an unused dashboard. Or when a groundbreaking concept falters in the face of real-world complexities. This article isn’t just about an ancient temple; it’s about understanding the “why” behind enduring masterpieces. It draws parallels to our own pursuits, and extracts strategic frameworks that can transform our digital aspirations into tangible, impactful realities.

Prambanan Temple, a UNESCO World Heritage site nestled in the heart of Java, stands as a testament to human ingenuity, spiritual devotion, and architectural mastery. More than just a collection of ornate stone structures, it embodies a profound paradox. It is a static, silent monument that speaks volumes about dynamic cultural shifts. It is also a rigid architectural framework that expresses fluid spiritual narratives, and a physical manifestation of an ethereal quest for divinity. As a masterpiece of Hindu architecture, its very existence in Java, a land deeply influenced by indigenous beliefs and later by Islam, presents a fascinating study in cultural synthesis and enduring heritage. This article will delve beyond the surface, offering unique insights into its construction, its context, and the timeless lessons it holds for anyone striving to build something truly lasting.

Dissecting the Core Architecture

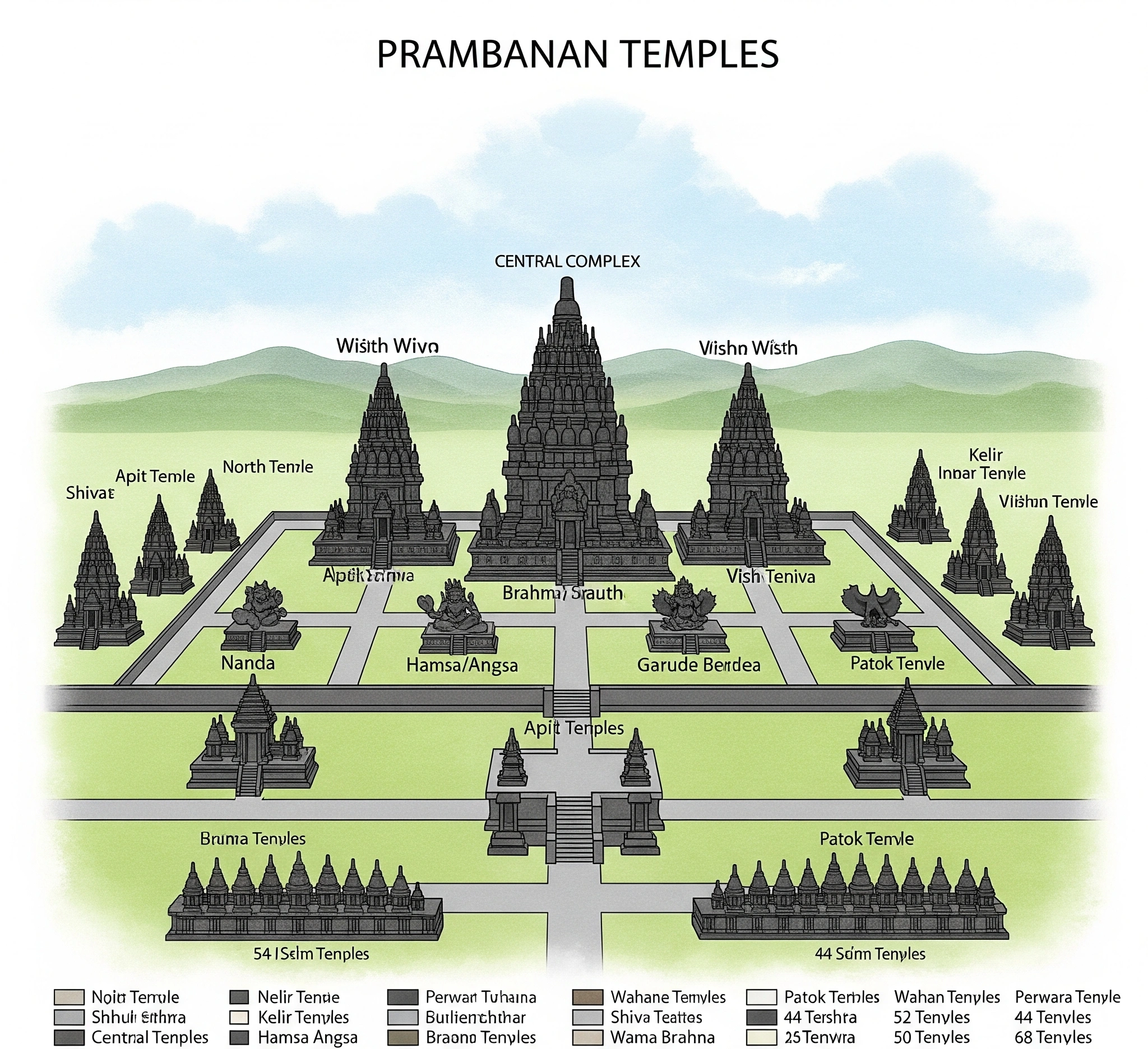

Prambanan, also known as Rara Jonggrang, is not merely a temple but a sprawling complex of over 240 individual temples. These are meticulously arranged to reflect the Hindu cosmological order. Its core architecture is a stunning embodiment of the Trimurti – the three principal Hindu deities: Brahma (the Creator), Vishnu (the Preserver), and Shiva (the Destroyer).

The Central Courtyard and Deities

The complex is oriented east-west, with the main entrance facing east, guiding visitors on a symbolic journey. At the heart of the complex lies the central courtyard. This area houses the three towering main temples dedicated to the Trimurti, each facing east. The tallest, the Shiva temple, soars to an impressive 47 meters. It is flanked by the Brahma and Vishnu temples, each reaching 33 meters. Directly opposite these, facing west, are three smaller wahana (vehicle) temples. These are dedicated to the respective mounts of the deities: Nandi (Shiva’s bull), Hamsa (Brahma’s swan), and Garuda (Vishnu’s eagle). The entire central courtyard is enclosed by a wall. Beyond it, two concentric rows of 224 smaller perwara (ancillary) temples complete the grand design.

Architectural Style and Narrative Reliefs

The architectural style is distinctively Hindu-Javanese, characterized by its towering, slender spires and intricate carvings. Each temple is adorned with bas-reliefs depicting scenes from the Hindu epics, primarily the Ramayana and Bhagavata Purana. For instance, the Ramayana reliefs, particularly on the inner balustrade of the Shiva temple, are read in a clockwise direction (pradakshina). This guides the devotee through the epic narrative as they circumambulate the temple. This integration of narrative art with architectural space is a hallmark of Prambanan’s genius.

Construction Materials and Techniques

The construction utilized volcanic stone, primarily andesite. This stone was expertly cut and fitted without mortar. The precision of the interlocking stones, often featuring a ‘dovetail’ joint system, allowed for remarkable structural integrity. Consequently, these massive structures could withstand centuries of seismic activity and volcanic eruptions. The temples are built on elevated platforms, a common feature in ancient Javanese architecture. This provided both structural stability and symbolic elevation. The meticulous planning, the sophisticated understanding of materials, and the sheer scale of the undertaking speak volumes about the advanced engineering and organizational capabilities of the Mataram Kingdom in the 9th century.

Understanding the Implementation Ecosystem

The construction of Prambanan Temple was not merely an architectural feat. It was a profound socio-political and religious undertaking, deeply embedded within the ecosystem of the 9th-century Mataram Kingdom. Its emergence marked a significant shift in the religious landscape of Java. This moved from the predominantly Buddhist influence (as seen in the nearby Borobudur Temple, which you can explore further at https://javanese.web.id/borobudur-spiritual/) back towards Hinduism, particularly the worship of Shiva. This shift was likely driven by the ruling Sanjaya dynasty. They sought to solidify their power and legitimacy through the patronage of grand Hindu temples, asserting their spiritual authority and cultural identity.

Key Factors in Implementation

The “implementation ecosystem” of Prambanan involved a complex interplay of factors:

- Political Will and Patronage: The sheer scale of Prambanan required immense resources and sustained political will from the ruling elite. Kings like Rakai Pikatan and Rakai Balitung are often credited with its construction. This reflects a deliberate state-sponsored project to establish a new religious and political center.

- Skilled Labor and Craftsmanship: The construction demanded a vast workforce of highly skilled stone carvers, sculptors, masons, and engineers. The intricate bas-reliefs and the precise interlocking stone construction point to generations of accumulated knowledge and specialized training. This was a centralized effort, likely drawing talent from across the kingdom.

- Resource Mobilization: Quarrying and transporting massive quantities of volcanic stone from nearby mountains (such as Mount Merapi) to the construction site was a monumental logistical challenge. It required organized labor and efficient transportation networks.

- Religious and Philosophical Foundations: The temple’s design, iconography, and narrative reliefs were not arbitrary. Instead, they were deeply rooted in Hindu scriptures, cosmology, and philosophical tenets. Priests, scholars, and spiritual leaders played a crucial role in guiding the artistic and architectural expression, ensuring doctrinal accuracy and spiritual resonance.

- Cultural Context: The temple’s aesthetic, while distinctly Hindu, also incorporated local Javanese artistic sensibilities. This resulted in a unique blend. This cultural synthesis allowed the new Hindu expressions to resonate with the existing Javanese population.

- Environmental Factors: The location in a tectonically active and volcanically rich region meant that the builders had to contend with natural hazards. The temple has suffered significant damage from earthquakes and volcanic eruptions over centuries, notably the 2006 Yogyakarta earthquake, which caused considerable structural damage. Its resilience, despite this, speaks to the robustness of its original design.

Challenges and Modern Preservation

The challenges of adoption and preservation for Prambanan are ongoing. After its decline in the 10th century (possibly due to a shift in the capital or a major volcanic eruption), the temple lay abandoned and fell into ruin for centuries. Slowly, it was reclaimed by the jungle. Its rediscovery and subsequent restoration efforts began in the early 20th century and continue to this day. This represents another layer of “implementation.” This modern effort involves archaeological science, conservation techniques, and international cooperation. It highlights the continuous challenges of preserving such a grand heritage in the face of natural decay and modern development. The story of Prambanan is thus a continuous narrative of creation, decline, and resurgence. It reflects the dynamic interplay between human ambition, natural forces, and cultural evolution.

Decoding the Ramayana Reliefs

Imagine we are tasked with a “project simulation.” Our goal is not to build Prambanan, but to fully comprehend and interpret one of its most intricate features – the Ramayana bas-reliefs on the Shiva temple. This isn’t a simple task of reading. Instead, it’s a deep dive into historical context, artistic intent, and cultural nuances. It’s akin to debugging a complex legacy system where the original developers are long gone.

Our initial “dashboard” (the temple itself) presents a magnificent, but overwhelming, array of carvings. The “problem” is immediate: how do we extract meaningful “data” (the story) from these “code blocks” (individual panels)? Often, they are weathered, partially damaged, or culturally opaque to a modern observer.

Data Collection & Initial Assessment (The “Failed” First Pass)

We begin by meticulously photographing each panel, creating a digital record. Our first attempt at interpretation might involve simply reading a modern translation of the Ramayana and trying to match it to the scenes. However, this often leads to frustration:

- Missing Context: Why are certain scenes emphasized? Why are some characters depicted in a particular way?

- Ambiguity: Some panels are abstract or damaged, making direct correlation difficult.

- Cultural Disconnect: The nuances of 9th-century Javanese Hindu iconography are not immediately apparent. For instance, the depiction of Ravana might differ subtly from classical Indian interpretations, reflecting local artistic traditions.

This initial, superficial “read” is akin to looking at a complex codebase without understanding its architecture, dependencies, or the design patterns used. We see the lines of code, but the logic behind them remains elusive. This leads to a “dashboard that’s unused” because it doesn’t provide actionable insights.

Phase 2: Deep Dive into “System Architecture” (Historical and Art Historical Analysis)

To move beyond the superficial, we must delve into the “system architecture” of the reliefs. This involves:

- Comparative Analysis: We study other Ramayana depictions from the period (e.g., in India or other parts of Southeast Asia) to identify commonalities and unique Javanese interpretations.

- Textual Research: We consult ancient Kawi (Old Javanese) texts, inscriptions, and religious scriptures that might have influenced the sculptors. This is like finding the original design documents and architectural blueprints.

- Iconographic Study: We seek to understand the specific mudras (hand gestures), asanas (postures), attributes (objects held by deities), and costumes that convey specific meanings within Hindu art.

- Spatial Context: We recognize that the reliefs are not isolated panels but part of a continuous narrative designed to be experienced as one circumambulates the temple. The placement of certain scenes might be deliberate, guiding the devotee’s spiritual journey.

The “Failure” as a Catalyst for Deeper Understanding:

Our initial “failure” to fully grasp the reliefs highlights a crucial lesson in any complex project: superficial understanding leads to incomplete solutions. The “unused dashboard” isn’t a failure of the data, but rather a failure of our approach to interpret it. Only by immersing ourselves in the historical, cultural, and artistic “code” can we begin to unlock the true “functionality” and “meaning” of Prambanan’s narrative art. This iterative process of initial assessment, recognizing limitations, and then diving into deeper research and comparative analysis, is a practical framework for anyone tackling complex systems, be they ancient temples or modern AI architectures. Ultimately, it teaches us that true expertise comes from acknowledging what we don’t know and relentlessly pursuing the underlying logic.

The Paradox of Resilience

The most profound and often overlooked insight into Prambanan Temple lies in its paradox of resilience. How could a structure built from unmortared stone, in one of the world’s most seismically and volcanically active regions, endure for over a millennium? It repeatedly collapsed and was painstakingly reassembled. This is the ‘open code’ moment, revealing a strategic framework for enduring systems.

Most discussions of Prambanan focus on its artistic beauty or religious significance. However, the true marvel is its inherent “design for resilience” – not through rigid, unyielding strength, but through a sophisticated understanding of flexibility and modularity.

The Core Paradox: Flexibility in Stone

- Flexibility in Rigidity: The interlocking stone system, while appearing rigid, actually allows for a degree of movement. Unlike modern concrete structures that crack under seismic stress, Prambanan’s individual blocks can shift slightly against each other, thereby dissipating energy. When an earthquake strikes, the temple essentially “shakes apart” rather than shattering. It then falls into a pile of identifiable blocks.

- Modular Design for Reassembly: Each temple is composed of thousands of precisely cut and numbered blocks. This modularity, though perhaps not intentionally designed for post-disaster reassembly, proved invaluable during its modern restoration. Archaeologists and conservators could meticulously reconstruct the temples, block by block, like a giant, ancient LEGO set. This is in stark contrast to structures that crumble into unrecognizable rubble.

- The Cycle of Destruction and Rebirth: Prambanan has been repeatedly damaged by earthquakes (notably in 16th century and 2006) and volcanic eruptions (especially from nearby Mount Merapi). Yet, each time, its very design facilitated its eventual rebirth. Therefore, the “failure” of collapse was not terminal, but a phase in its long lifecycle.

Lessons for Modern Systems

This concept of “resilience through modularity and predictable failure” offers a powerful lesson for modern technology. In software development, we often strive for monolithic, unbreakable systems. However, the ‘open code’ of Prambanan suggests a different, more robust approach:

- Microservices Architecture: Break down complex systems into smaller, independent, and easily replaceable components. If one microservice fails, the entire system doesn’t crash; instead, it can be isolated and rebuilt.

- Graceful Degradation: Design systems that can continue to function, perhaps with reduced capacity, even when components fail. Prambanan doesn’t shatter; it degrades into reconstructible parts.

- Observability and Recovery: Just as archaeologists meticulously map and number fallen blocks, modern systems need robust logging, monitoring, and automated recovery mechanisms to understand failures and facilitate rapid restoration.

- Antifragility: Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s concept of antifragility – systems that gain from disorder – perfectly describes Prambanan. Each collapse, while destructive, provided new insights for future restoration, making the understanding of the temple more robust over time.

The unique insight is that Prambanan’s enduring presence isn’t just a testament to its initial construction. Rather, it’s due to its inherent “antifragile” design that allowed it to survive and be reborn through centuries of natural chaos. It’s a living paradox: a static monument that embodies dynamic resilience, offering a lesson in building systems that don’t just resist failure, but learn from it.

An Adaptive Action Framework from Ancient Stones

Drawing lessons from Prambanan’s enduring legacy, we can formulate an Adaptive Action Framework. This framework is applicable to complex projects, whether in technology, heritage preservation, or organizational development. It shifts our mindset from aiming for perfect, static solutions to embracing dynamic resilience and continuous adaptation.

1. Embrace Modular Design for Predictable Failure:

- Ancient Wisdom: Prambanan’s interlocking, unmortared stones allowed for movement and reassembly.

- Modern Application: Design systems (software, organizational structures) with modular components. Anticipate that individual parts will fail. The goal isn’t to prevent all failures, but to ensure that failures are localized, recoverable, and don’t cascade into catastrophic system collapse. Consider microservices, independent teams, and decentralized decision-making.

2. Prioritize Observability and “Block Mapping”:

- Ancient Wisdom: The ability to identify and reassemble fallen blocks was crucial for Prambanan’s restoration.

- Modern Application: Implement robust monitoring, logging, and analytics. Understand the “state” of your system at all times. When failures occur, have mechanisms to quickly identify the root cause, isolate the issue, and map out the affected components for efficient recovery. This is your “digital block mapping” system.

3. Cultivate an “Antifragile” Mindset:

- Ancient Wisdom: Prambanan gained strength and understanding from its repeated collapses and restorations.

- Modern Application: View setbacks and failures not as endpoints, but as opportunities for learning and improvement. Build feedback loops into your processes that allow your system (and your team) to adapt and become more robust in response to stress and volatility. This means fostering a culture of psychological safety where failures are analyzed, not punished.

4. Understand the “Ecosystem” Beyond the “Code”:

- Ancient Wisdom: Prambanan’s construction was deeply intertwined with political, religious, cultural, and environmental factors.

- Modern Application: Recognize that any project exists within a broader ecosystem. Technical solutions alone are insufficient. Consider the human element (user adoption, team dynamics), the organizational context (stakeholder buy-in, budget constraints), and external factors (market shifts, regulatory changes). A “perfect” technical solution that ignores its ecosystem is destined to become an “unused dashboard.”

5. Design for Longevity and Iterative Evolution:

- Ancient Wisdom: Prambanan was built to last, but its “life” has been one of continuous evolution – from initial construction to centuries of abandonment, rediscovery, and ongoing restoration.

- Modern Application: Think beyond the initial deployment. Design for maintainability, scalability, and future adaptability. Plan for iterative improvements, refactoring, and potential “reconstructions” as technology evolves or requirements change. A system that can be easily modified and updated is more likely to endure.

This framework, inspired by the silent lessons of Prambanan, urges us to move beyond simplistic notions of “success” and “failure.” Instead, it champions a dynamic approach where resilience is built into the core, where learning is continuous, and where the ability to adapt and rebuild in the face of inevitable challenges defines true mastery.

A Vision for Enduring Creations

Prambanan Temple, with its towering spires and intricate carvings, stands not just as a monument to a bygone era but as a living testament to the enduring power of vision, dedication, and adaptive design. Its story—of creation, decline, rediscovery, and meticulous reconstruction—offers a profound narrative for anyone engaged in the complex act of building.

In our pursuit of digital transformation, we often become fixated on the latest tools, the most efficient algorithms, or the most dazzling interfaces. Yet, the true measure of a masterpiece, whether ancient or modern, lies in its ability to withstand the test of time. It must adapt to unforeseen challenges, and continue to resonate with meaning across generations. Prambanan teaches us that resilience isn’t about avoiding collapse, but about designing for recovery. It shows that true innovation often lies in the elegant simplicity of modularity. Furthermore, the deepest insights emerge when we dare to look beyond the surface, into the underlying “code” of existence itself.

As we continue to shape our digital future, let us carry the wisdom of the ancient architects of Prambanan. Let us build systems that are not only powerful but also adaptable, not just efficient but also enduring, and not merely functional but deeply meaningful. For in the paradox of stone and spirit, we find the blueprint for creations that truly last.

Ditulis oleh [admin], seorang praktisi AI dengan 10 tahun pengalaman dalam implementasi machine learning di industri finansial. Terhubung di LinkedIn.